Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: e-commerce

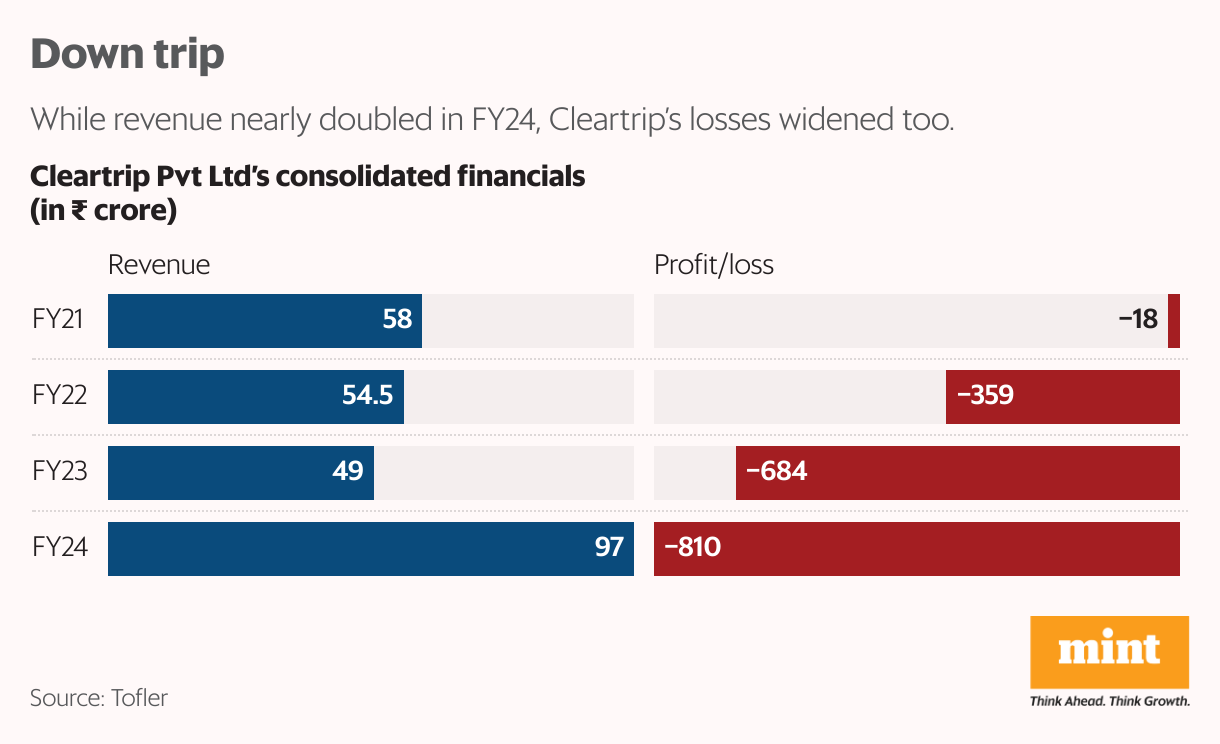

Spending ₹988 crore to earn ₹97 crore—20 years on, Cleartrip still has no flight plan

The high-gloss ad, released in mid-2024, was Cleartrip’s big push to grab mindshare in a crowded travel booking market. Over the last couple of years, the company has been trying to make a comeback with such promotions.

But while it took a good swing, a look at the company’s FY24 financials, released a few months back, reveals many misses: Cleartrip has been burning through cash without a clear return on investment. The company spent ₹988 crore to earn just ₹97 crore, with ₹500 crore spent just on discounts, as per the consolidated financials of the company, sourced from Tofler.

The two-decade old online travel agency’s (OTA) operating revenue remains stuck below ₹100 crore, even as its losses have ballooned past ₹800 crore. Where others in the travel industry, such as MakeMyTrip, Ixigo and EaseMyTrip are turning profits, Cleartrip is sinking deeper into the red.

Last Thursday, the company appointed Manjari Singhal as its new chief growth and business officer, less than a year after her predecessor was appointed. On her shoulders fall the onerous task of turning the company around.

Cleartrip, which was acquired by Flipkart in 2021, is far from where the e-commerce giant expected it to be—despite its aggressive discounts and star-studded campaigns. Industry insiders point to years of misplaced priorities and strategic missteps that have left Cleartrip gasping for revenue.

A burn strategy can work initially to aggressively capture market share through heavy discounting and customer acquisition. But when expenditure vastly outpaces revenue, it threatens long-term financial stability and requires a shift toward a more balanced cost structure, said Mit Desai, practice member, travel and tourism, at Praxis Global Alliance.

While offering discounts is a straightforward practice in the travel industry, an industry expert points out that you can use this strategy at the early growth stage, not at a stage where you need to consolidate your margins and look at your profitability.

Over-reliance on discounts can create short-term traction but doesn’t necessarily build loyalty or long-term value, said Harish Khatri, founder and MD at India Assist, a travel assistance company. “The strategy may have been adopted to stay visible in a crowded market, but eventually, the fundamentals have to make sense.”

Today, the Flipkart-owned travel platform finds itself at a crossroads, raising questions about its strategy, sustainability, and market fit.

The brand

Founded in 2006 as a hotel and air aggregator by Stuart Crighton, Hrush Bhatt, and Matthew Spacie, Cleartrip was quick to gain traction.

With many travel startups being built, that era saw a major shift from offline travel agents to online travel agencies. MakeMyTrip (2000), Yatra (2006) and Ixigo (2007) are the biggest companies in the space.

Over the last two decades, Cleartrip has built a brand for itself in the travel industry. It’s a company known for its excellent user interface and user experience (UI/UX).

View Full Image

A screenshot from Cleartrip’s home page.

Despite all the focus on building a great product, after a few years, the wheels started to come off. “When you get these awesome reviews on UX UI and get carried away, you will start focusing on UX UI rather than on transactions,” a former senior executive of the company told Mint. “A lot of times, If I would talk about moving this button here, or trying to say this kind of flow will give us higher transactions, it was shot down saying, we can’t compromise on UI UX.”

The big miss

In the early years, the biggest companies in the space had a majority of their business coming from air travel. Investments were drying up and around 2010-11, all of them started to focus on building the hotels business—a more lucrative vertical with about 18-20% margins, compared to the 0.6-0.7% margin in air ticketing, according to industry estimates. It is a common understanding that while air travel drives the top line, hotels are what bring in money.

Cleartrip, according to industry executives and former employees, continued to focus on flights. Around 2014-15, after a boom of 6-7 years, OTAs had more or less settled down into their revenue models. Everybody in the ecosystem understood that flights were a commodity business—whoever sold cheapest would succeed—according to a former senior executive.

Cleartrip did not respond to multiple requests for an interaction or a detailed questionnaire sent over email.

“MakeMyTrip understood it fairly early, and they built a brand you just can’t compete with. However, Cleartrip had an overdependence on flights, where 85-90% of the revenue was coming from flights. But they just couldn’t take the risk involved in diluting focus from flights and pushing on building hotels and non-flight businesses. Their risk appetite was very, very limited,” he said.

Cleartrip started with direct contracts with hotels, but the number of hotels kept shrinking. Eventually, it started sourcing hotels from other platforms such as MakeMyTrip and Yatra. “They switched off and closed down their own supply team around 2018,” a former executive recalled. The hotel business was revived only in 2023.

Air travel is a standard product where a customer is just looking for a seat to travel from one place to another at a certain price and at a certain time. The customer knows what he/she will get, except for delays, but otherwise, the in-flight experience is standard, with only a few choices with regard to airlines. Hotels, however, is a business that requires a very complex decision-making process.

“You need a very small team to manage the supply side of the air business. When it comes to the hotel business, the supply is highly disintegrated. Pan India, you have a large number of accommodations. There are five-star, four-star, three-star, two-star, and unrated hotels. Many of them adopt technologies, and many don’t. So, even the supply curation and ensuring you’ve got the right inventory, product pricing, content—you need a big team,” an industry executive explained.

“To give you an example, a while back, when there were 5-6 people to manage the air supply at Cleartrip, there were almost 150-200 people to manage the supply of hotels,” a former executive noted.

Big daddy

Cleartrip is not a leader in any category. According to data from research agency VIDEC consultants, It does not have any market share in the rail and bus segments based on gross booking value. It is a distant second in the air category after MakeMyTrip, with about 14% market share, and third in hotels with about 2% market share.

Clearly, Cleartrip is still trying to find its footing when it comes to defining its true area of expertise. Market experts say Ixigo gets huge traffic because of train tickets and that traffic can then be utilized for air or hotel and other products. Yatra has become a specialist in corporate business. The biggest of them all is MakeMyTrip, which has a finger in every pie.

About eight years ago, MakeMyTrip acquired Goibibo, in a significant consolidation move. It was a big turning point, according to industry watchers and former employees.

“Goibibo came in with huge discounting and huge money power. They went ahead with very aggressive discounting in the online domain, which none of the other guys were able to keep up with,” said a former senior executive.

Goibibo was launched in India in 2009 by the ibibo Group, which was backed by South African tech giant Naspers. While it started as a social networking and gaming platform, it pivoted to online travel bookings, focusing on flights, hotels, and bus bookings around 2012. Four years later, MakeMyTrip acquired the company.

“MakeMyTrip launched holidays in 2007 and the first two years were brutal but Deep Kalra (founder) said this is one space we want to be in because it gives me double-digit margins and the engagement that you do with clients is far better than your engagement when you do flights,” said an industry executive.

View Full Image

A file photo of Deep Kalra, founder MakeMyTrip. (Mint)

The company continued to invest in that business for 6-7 years and kept losing money. Later, it figured out how to run the holiday business in a lean and mean way. Cleartrip, on the other hand, say industry watchers, was lacking in both clarity, speedy execution, patience and capital.

Acquisition by Flipkart

On paper, what Flipkart perhaps found appealing about Cleartrip is that it would be able to get high gross margin value (GMV) transactions without any complexity of actual logistics and operations, as everything is e-delivered, an industry executive said.

But the travel business did not deliver the kind of hockey stick growth that Flipkart anticipated. “It is a lifestyle business and not everybody can afford a flight ticket or a hotel in India. Typically, you are at the tip of the pyramid in terms of the total customer set,” the former executive cited above explained. “But if you’re selling a mobile phone, which is one of the highest selling categories in e-commerce, they’re at the bottom of the pyramid, with everybody buying a phone today.”

Moreover, the integration with the parent took longer than expected. When Flipkart acquired the company in 2021, travel had started to rebound but both the companies were still locked in the integration.

The e-commerce platform tried to operate Cleartrip the e-commerce way, with a lot of talent from its marketplace model being moved to the travel company. Almost 90% of the workforce, including the management and the second line, were from the marketplace team, with only 5-10% having a travel background, a former executive claimed. That did not pan out well.

When Flipkart acquired Cleartrip in 2021, travel had started to rebound but the two companies were still locked in the integration.

“When they acquired Cleartrip, they got carried away by the glitz of the travel business, airlines, hotels and moved some of their Flipkart, Myntra, senior management into Cleartrip. They did it like a fashion or e-commerce brand and the whole treatment backfired,” one former senior executive noted. “I’m not saying only travel guys can build travel businesses, but you need to have the right balance of industry folks and e-commerce folks,” another executive said.

The thing that Cleartrip needs the most is vision and leadership, according to industry executives. The company has seen a significant churn at the top with former Cleartrip CEO Ayyappan R. stepping down after an 11-year tenure with the Flipkart Group, and CFO Aditya Agarwal resigning soon after.

Singhal is now replacing Anuj Rathi, who the company says is moving on to pursue new opportunities. Singhal led the Beauty, FMCG, and General Merchandise business at Flipkart.

Rathi is leaving the company less than a year after he joined Cleartrip. Notably, he, too, came with an e-commerce background, with a career spanning two decades in tech and e-commerce, including roles at Swiggy and Jupiter Money.

Renewed focus

Hotels is the only category where Cleartrip could make a comeback. It remains a big opportunity as 70-75% of the business is still offline, meaning it can be converted to online.

View Full Image

A screenshot from Cleartrip’s hotels page.

In recent years, the hotel segment has indeed become the top priority for Cleartrip. The company is also working on building its corporate as well as cab and bus segments. In 2023, Ayyapan R., the then CEO of the company, said the new categories—hotels, bus and cabs—would contribute to over 50% of the business.

Akash Nigam, co-founder of travel agency Mansa Travels says that the online travel market is at a strategic inflexion point where customer acquisition costs must align with lifetime value metrics.

“Cleartrip’s opportunity moving forward lies in strategically expanding into under-served segments like series and fixed departure flights, which could drive consistent traffic from business and group travellers seeking specialized inventory,” Nigam added.

“To gain momentum, a company must pivot toward a sustainable model by focusing on high-margin segments (for example, business travel and premium packages), leveraging digital tools and AI for targeted customer engagement, and aggressively rationalizing costs to drive long-term profitability,” said Praxis Global Alliance’s Desai.

For Cleartrip, that is the challenge. The company appears to have woken up belatedly to hard business realities. But it still needs to make the right calls to fly out of the turbulence of recent years and get into cruise mode.

Real Estate: China’s loss is India’s gain as CapitaLand shifts gears

But on a Friday afternoon last month, ITPB, which is dotted with all kinds of commercial buildings, including a mall, a premium hotel, recreational facilities, and the offices of the world’s biggest multinationals, was teeming with people. Some of the older edifices in the 30-year-old park are now getting a facelift. And in one corner, a massive parking lot has been turned into a construction site, where nearly 2.4 million sq. ft of new office space is coming up.

ITPB epitomizes a larger story that is playing out across India. Office goers are back and demand for offices is booming. And Singapore-headquartered CapitaLand Investment (CLI), which operates ITPB and is its majority owner, is making the most of this renewal as part of a concerted India play.

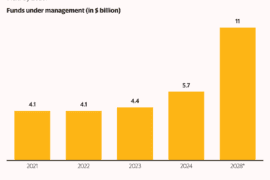

Last September, the Singaporean company announced that it was looking to more than double its $5.7 billion funds under management in India by 2028. The new investments will be in existing businesses—office parks, logistics and industrial real estate, data centres, and lodging—as well as in new areas such as renewable energy and private credit for real estate.

CLI already has a number of commercial projects under construction or in the pipeline in cities across India.

The real estate investor’s decision to have a broader presence in the country has been prompted to a large extent by the growth prospects of the Indian economy. But that isn’t the sole reason. CLI has also been pushed to diversify its Asian investments in the face of mounting challenges in a key market.

Beyond China

The term ‘China + 1’ was coined to describe a business strategy that involves diversifying manufacturing and sourcing beyond China. Drawn by the Asian giant’s low labour and production costs, as well as its enormous domestic market, many multinationals had invested huge sums in the country. But in the wake of trade tensions, increasing labour costs and extended covid lockdowns, many of them made a conscious decision to reduce their dependence on China and find alternative supply chain centres.

While it is not a manufacturer of goods, CLI, part of CapitaLand Group, a diversified real estate conglomerate, has taken a leaf out of the China + 1 playbook. Over the decades, it invested in everything from office spaces to malls in China. The country is, in fact, CLI’s second biggest market after Singapore, its home turf. But China’s real estate crisis, which began in 2021 with a default by housing developer Evergrande Group, has taken a toll on some of those investments.

View Full Image

China’s real estate crisis began in 2021 with a default by housing developer Evergrande Group. (Reuters)

Last November, citing the company’s investor day presentation, it was widely reported by foreign media that CLI would moderate its China exposure from 27% of its funds under management to 10-20% by 2028. The reports also noted that the company had warned of likely losses as it sought to emerge from the real estate debacle. While moderating its presence in China, CLI said it would step on the gas in markets such as India, Japan, Korea and Australia.

“Many APAC investors are following the ‘anything but China’ strategy. As a result, investors in Singapore, Japan and even Korea will reallocate capital, a part of which will come to India,” said Shobhit Agarwal, managing director and chief executive at advisory firm Anarock Capital. “Singaporean investors such as CapitaLand Investment, for instance, are looking for deeper value and are taking long-term bets.”

While still making up only a modest part of its overall funds under management, India certainly appears to be a big part of CLI’s plans as it looks to diversify beyond China.

Full speed ahead

Barring a few hotel assets, CLI didn’t have much of a presence in India before 2019. That changed when it merged with Ascendas-Singbridge to create one of the largest real estate groups in Asia. Ascendas, a Singapore government-backed developer, had in fact begun its journey in India in 1994 with ITPB. The tech park in Whitefield had been conceived a couple of years earlier, when then prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and then Singapore prime minister Goh Chok Tong mooted the idea of developing infrastructure for the IT industry. Soon after, a consortium led by Ascendas, the Tata Group (which later sold its stake to Ascendas), and the Karnataka Industrial and Area Development Board, which owned the land, started construction on the tech park.

View Full Image

An under-construction office space at the International Tech Park Bangalore, operated by CapitaLand Investment. (Madhurima Nandy/Mint)

As India turned into a global IT services outsourcing destination, the Singaporean company steadily built more such tech parks around the country. Today, its footprint has expanded beyond Bengaluru to Chennai, Hyderabad, Pune, Mumbai, and Gurugram. Around 250,000 people work in these parks.

However, because of its measured approach in building its India property business, Ascendas-Singbridge was outpaced by larger and more aggressive US and Canadian investors such as Blackstone Group and Brookfield.

Now, CLI, which has taken over the reins after merging with Ascendas-Singbridge, wants to catch up. In 2024, India constituted around 7% of the company’s funds under management. The goal is to make that at least 10% by 2028.

CLI is 53% owned by Singapore state investor Temasek Holdings. Last year, Temasek, which has directly invested in multiple sectors in the country, said India was its best-performing market.

“India has a lot going for it,” Sanjeev Dasgupta, CEO, CapitaLand Investment India, told Mint. “CLI has ambitious growth targets and expansion plans for the company overall. Given that India is growing so rapidly, CLI wants it to play a bigger part in that growth journey.”

To this end, the company plans to take both the organic and inorganic routes, building from the ground up and making acquisitions. The money for all this will come from CLI’s three capital pools in India. The first is its balance sheet, from which long-gestation projects and land acquisitions are funded. The second is private funds that bring in institutional investors for greenfield developments. And finally, from the Singapore-listed entity CapitaLand India Trust, which focuses on income-generating assets and acts much like a real estate investment trust (Reit).

“The pace of growth will be faster. The way that the office, logistics, and data centre markets have taken off in India, it’s much easier to convince investors today to invest in India-focused funds,” said Dasgupta.

Office expansion

Many global capital providers were in a bit of a wait-and-watch before committing to the office sector in India post pandemic. Now that the sector has picked up, analysts believe investments will pour in from Singapore, Japan and even Korea.

CLI India currently has 13 office parks, spanning 25 million sq. ft, which it owns along with CapitaLand India Trust, the first listed India property trust in Asia, and private fund platforms. Many more are being built—CLI has a development pipeline for 14.3 million sq. ft of office parks, which will come up in the next three-four years across cities to address the demand for premium office spaces.

CLI India currently has 13 office parks, spanning 25 million sq. ft, which it owns along with CapitaLand India Trust, the first listed India property trust in Asia, and private fund platforms.

In 2024, office leasing recorded a historic high of 79 million sq. ft across nine cities, setting a new benchmark for leasing activity, as per property advisory CBRE India data.

Ram Chandnani, managing director, advisory and transaction services, at CBRE India, said that while rupee volatility remains a concern for foreign investors, their expectations on returns have been met in terms of office investments. That is certainly true in the case of CLI. “India is the best-performing office market portfolio in all of CLI. China would always outshine India, but that has changed in the last couple of years,” Gauri Shankar Nagabhushanam, CEO, CapitaLand India Trust, told Mint. “Last year witnessed a record high in office leasing, making India the No. 1 office market in absorption [leasing]. Investors are looking at India more keenly than before.”

Global capability centres (GCC) account for 44% of CLI’s client portfolio in office parks, where it hosts companies such as Amazon, Deloitte, Bristol Myers, Warner Brothers and Xerox, among others. Nagabhushanam said the GCC office leasing momentum will continue to be a major driver for the company.

Last year, the company raised its latest office parks fund, CapitaLand India Growth Fund II ( ₹3,255 crore corpus). New investments in the office segment will be made from this fund, as well as from CapitaLand India Trust.

The logistics bet

As an asset class, India’s office segment has undergone a major shift from standalone buildings to corporate business parks. In warehousing and logistics, however, the move from inefficient to efficient space is still ongoing. So, for institutional investors with a long growth runway, logistics was a natural choice after the office segment.

After developing business parks for close to two decades, Ascendas Firstspace, a logistics and industrial platform born out of a joint venture between Ascendas and Firstspace Realty (India), and now part of CLI, was launched in 2017. Two funds were raised in quick succession to expand the business. In 2018, Ascendas India Logistics Fund raised ₹2,480 crore, and in 2021, CapitaLand India Logistics Fund II raised another ₹2,480 crore.

The timing was just right. The demand for modern warehousing and industrial facilities was growing, thanks to an expansion in manufacturing activity, e-commerce, as well as other sectors. That led to a solid appetite among investors for good quality industrial assets.

In the span of a few years, the platform has emerged as the third largest in the country, after Indospace and Blackstone-owned Horizon Industrial Parks. Ascendas Firstspace has 11 million sq. ft of operational assets, across five facilities. It also has another 13-14 million sq. ft of under-construction projects and projects in the pipeline.

The demand for modern warehousing and industrial facilities is growing, thanks to an expansion in manufacturing activity, e-commerce, as well as other sectors.

So far, the expansion template has been in line with its office parks business strategy: to buy land, and then build and operate warehousing facilities and industrial parks. That could change. To grow faster, large players such as Blackstone are adopting a twin-pronged approach, where they are now building out their portfolio as well as acquiring ready assets to eventually monetize them. Ascendas Firstspace, too, is planning something similar.

“As we expand, we are looking to acquire ready, good-quality assets from other portfolios. We are looking to start that in the next couple of quarters,” said Aloke Bhuniya, CEO, Ascendas Firstspace. “We will do around 3-4 million sq. ft of greenfield development every year. Acquisitions will depend on market conditions and opportunities.”

Like the office sector, India’s logistics and industrial sector recorded an all-time high of 50.4 million sq. ft of net leasing last year, as per property advisory JLL India’s estimates, led by modernization of warehousing and industrial spaces and an increase in demand.

Beyond its core markets of Bengaluru, Chennai, Pune and the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), Ascendas Firstspace will also enter tier-II markets such as Lucknow and Ahmedabad thanks to rising consumption and disposable income trends making smaller cities attractive for e-commerce players.

E-commerce demand, which peaked in 2021 and then dropped sharply, made a moderate comeback of sorts in 2024. This year will see the return of e-commerce demand in the logistics space, Bhuniya said.

Having built large-format warehousing and industrial facilities, the company also plans to get into new products, such as in-city distribution centres, which are in demand due to the quick commerce boom.

Diversification push

In January, CapitaLand India Trust said it had signed a long-term agreement with a leading global hyperscaler for one of its data centres under development. A hyperscaler is a company that operates a global-scale cloud computing infrastructure.

Data centres, which have emerged as an attractive asset class for institutional investors, are the newest addition to CapitaLand India’s portfolio, a business it set up only in 2021. Globally, it has 27 data centres, to cater to the expansion needs of hyperscalers and enterprises. In India, it has four under development—in Navi Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad and Bengaluru—with a total gross power capacity of around 250 megawatts (MW).

After data centres, next in line are renewable energy and private credit for real estate. CLI will enter both these businesses via stake acquisitions, Dasgupta said.

View Full Image

A file photo of Sanjeev Dasgupta, CEO, CapitaLand Investment India.

For renewable energy, which would serve as an adjacency to its own data centres, it is evaluating such platforms or companies for a potential acquisition.

After the 2018 non-banking financial company crisis, there has been a shift in the real estate private credit business, creating space for new private contenders.

“We want to lend to projects at an early stage or those awaiting approvals. We are looking at opportunities to acquire an existing platform. We will put in seed money and raise third-party capital in the new fund management business,” said Dasgupta.

While things look promising, CLI will need to deliver in both existing and new businesses to meet its 2028 growth target. The expansion will also depend on access to capital.

Dasgupta, riding on CLI’s operational expertise over three decades, deep-pocketed sponsor support, and new funds, is brimming with confidence. “The stars have aligned with the market opportunities that have presented themselves in India,” he declared.